Fast-moving consumer goods major ITC was under attack recently reportedly for sending a notice to workers of its two food factories in Maharashtra and Karnataka, threatening “disciplinary action” and salary cuts if they didn’t turn up for work despite social distancing and safety precautions at workplace. An ITC spokesperson denies, saying the company paid full wages to its 50,000 workers in April. However, the case raises interesting questions about the rights of workers, especially under the prevailing circumstances with states planning unprecedented changes in labour laws.

Employment lawyer Atul Gupta, Partner at law firm Trilegal, says in the last one month, 20 of his clients have expressed concerns about non-availability of labour. “I am getting queries from corporates – Can I take disciplinary action against workers refusing to work? Can I refuse to pay them? Can I terminate their contract?, says Gupta.

With Unlock 1.0 kicking in and companies looking to ramp up production to make up for losses over the last two months, manpower shortage has emerged as a key concern. A number of employees have gone back to their villages and home towns. Some are not showing up due to fear of getting infected.

To enable companies to kick-start production, several state governments have announced relaxations in labour and employment laws. These changes are in two broad categories. First, exemptions from provisions of labour laws (Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat). Second, extension of working hours under the Factories Act, 1948 (Assam, Goa, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Odisha, Maharashtra, Uttarakhand and Punjab). Though some of these changes are being reviewed, state governments say flexibility in labour laws will help companies revive production with limited staff and encourage them to invest.

While industry has welcomed the initiatives, the changes have not gone down well with trade unions and workers. Even economic experts say government’s view that labour law reforms as remedy for all economic ills will not help. A lot more is required to be done, they add.

The Two Sides

Labour is in the Concurrent List of the Constitution. Almost 10 states have announced labour law reforms. In fact, Union Labour and Employment Secretary Heeralal Samariya had reportedly asked states to undertake these measures.

Considering that most bold reforms have been undertaken by states ruled by the BJP, experts say they are likely to have the Centre’s support. “Reforms announced by Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh and Assam are based on a common template. It is unlikely that they don’t have the Centre’s backing,” says Ravi Srivastava, Director, Centre for Employment Studies, Institute For Human Development (IHD).

Last month, the Uttar Pradesh government proposed suspension of all labour laws for the next three years, barring three (related to payment of timely wages, prohibition of bonded labour, and health and safety of workers). “The ordinance issued by the UP government is extremely wide. You cannot have no law,” says Srivastava of IHD. The proposal is awaiting approval from the President. If passed, employers will be able to choose whether to pay for overtime or not. They will also be able to decide whether to give paid holidays, gratuity or maternity benefits, or even compensation for termination. Workers will no longer have legal rights to approach the court. “Different codes under labour laws complement each other – Trade Union Act, Factories Act, Industrial Disputes Act, Contract Labour Act. They cannot be seen in isolation,” says Srivastava. For instance, if there is an accident in a factory, workers will not have any recourse to settle their grievances because reconciliatory machinery under the Industrial Disputes Act will be defunct.

Niti Aayog Vice-Chairman Rajiv Kumar agrees. He said recently that abolition of labour laws is not a reform and the Central government will protect interests of workers. Lohit Bhatia, President, Indian Staffing Federation (ISF), says, “Labour codes are about both job seekers and job givers. You cannot fluctuate from one extreme to another where legislation supports only one side for a few years and then another. It has to be collective bargaining. The reason for having tripartite agreements is that everyone – labourers, staffing firms and employers – is reasonably protected.”

While the ordinance passed by the Uttar Pradesh government doesn’t differentiate between old and new firms, Madhya Pradesh’s amendments focus on incentivising new factories. The new factories would benefit from Industrial Disputes Act exemptions, one of the biggest pain points for companies. This means as long as new factories set up a fair mechanism to investigate and settle disputes, they will enjoy significant flexibility without worrying about prosecution. Till August 2020, all industries will get relaxations from all provisions of the Factories Act, barring the clause on safety.

In addition, eight states (Maharashtra, Odisha, Goa, Uttarakhand, Assam, Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh) have given flexibility to companies under the Factories Act regarding number of daily and weekly working hours. Most of them have extended the hours from eight to 12 per day. The difference is that some are paying for the extra work while others aren’t. The 72-hour working week violates the International Labour Organization’s (ILO’s) Hours of Work (Industry) Convention, 1919, to which India is a signatory. India can have up to 60 working hours per week under the convention.

Among states, only Karnataka has adopted a balanced approach. It has proposed up to 10 hours of work a day (within ILO norms), and 60 hours (not 72) a week, for three months ending on August 21. Overtime wages will have to be paid (double the usual wage rate).

The changes have not gone down well with many, and have already been challenged in court. The country’s 10 largest Central trade unions have written to the ILO’s Director-General, Guy Ryder, highlighting the “virtual nullification of most of the substantive laws ? through state governments.”

Amarjeet Kaur, General Secretary, AITUC, says, “Without labour laws, all responsibility and accountability towards workers will be negated. It will give a free hand to organisations to exploit them.” According to Kaur, the Central government is using the lockdown to reduce bargaining power of workers and trade unions. Twelve hours of work plus travel time will put considerable pressure on workers and discourage women from entering the workforce, she adds.

A PIL filed by Pankaj Kumar Yadav in Supreme Court has challenged the decisions of Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat governments. The UP government withdrew the working-hour notification after a notice by the Allahabad High Court. The Rajasthan government also withdrew the notification extending working hours.

Flexibility Is Key

Change in laws via administrative orders or ordinances is susceptible to legal challenge and can lead to policy flip-flops, which discourages investors from making long-term bets on the country, say experts. “A consultative process by the Union government with states would have ensured uniformity of laws and buy-in from all stakeholders such as worker organisations and unions right in the beginning. This might have minimised scope for opposition and paved the way for acceptance of these changes,” says Virag Gupta, Supreme Court lawyer and Partner at law firm VAS Global.

Bhatia of ISF says flexibility in working hours is important as manpower shortage is likely to peak in July. “If the current pace of reverse migration continues, 2.5-3 crore workforce would have gone back to their villages and home towns. Sectors like manufacturing, construction and transport employ 9-11 crore people. So, every third employee would have gone back by the end of June. To restart work in these sectors in full shifts, flexibility is needed, but as long as the extensions are time-bound, and reforms do not impinge on workers’ rights.”

Most notifications for work-hour extension are applicable for the next two to three months.

Longer working hours is not a new thing. Earlier, workers would willingly put in longer hours to earn extra money. “If laws provide workers an avenue to get paid for extra hours, it will work in their favour,” says Gupta of Trilegal.

Also, longer shifts will help firms implement social distancing norms. “Running at full capacity and implementing social distancing norms will make it difficult to have three shifts of eight hours. Instead, have two shifts of 11 or 12 hours each,” adds Gupta. There is a provision for a one-hour break between shifts for sanitising the premises.

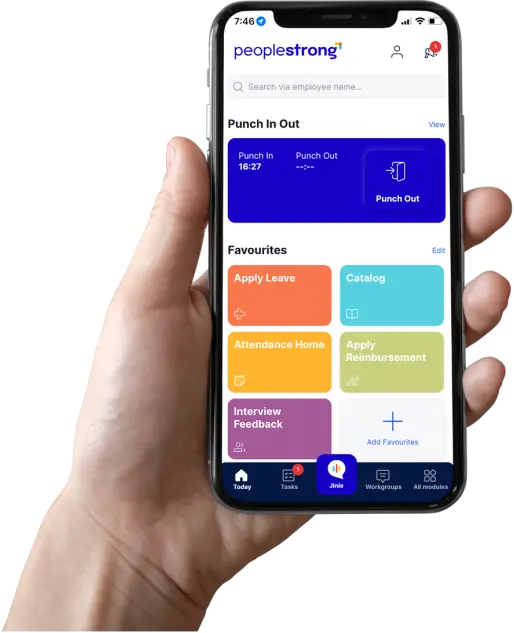

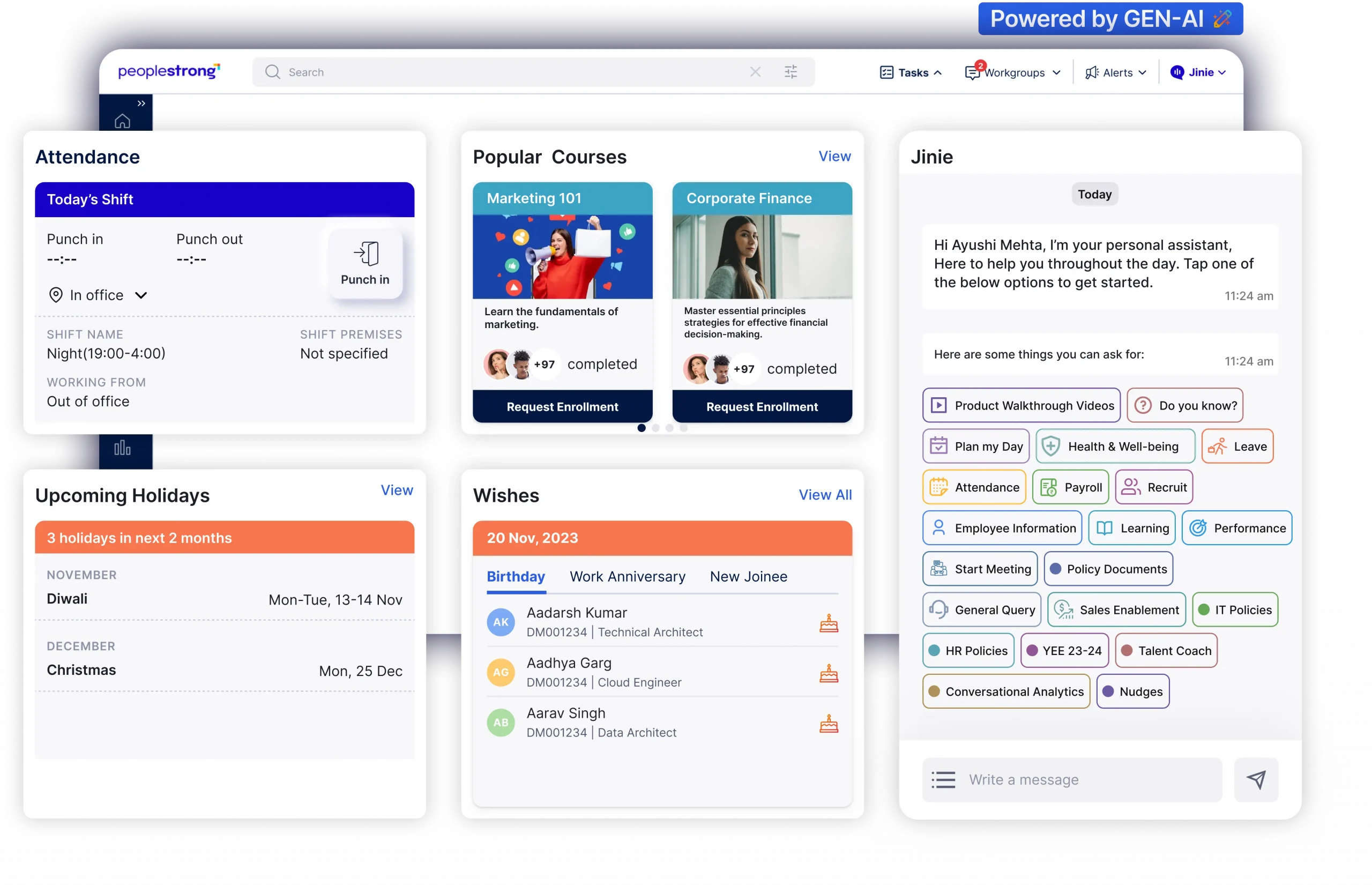

But payment of overtime wages will put additional stress on firms, already grappling with cash crunch, says Vikas Sapra, Vice President, Technology Operations, PeopleStrong. “It will be difficult to pay extra immediately. Many firms might have to take additional loans to pay higher salary costs.”

Unified Approach

The big question is — will it help firms? Labour law reforms are required but they need to be looked at holistically. Sougata Roy Choudhury, Executive Director, Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), says the number of changes is a concern. “Organisations work across the country and cannot have a variety of labour laws. There is a need to centralise them. Even labour laws under states should be based on a unified model.”

“If you add all permutations and combinations of all the Central and state laws, there are more than 20,000 sections for which firms need to submit applications for,” says M.S. Unnikrishnan, Chairman, CII National Committee on Capital Goods and Engineering, and MD, Thermax.

The Centre has been working on four Labour Codes that will subsume all 44 Central laws. The Code on Wages has been adopted by Parliament; the rest are awaiting approval. “We need to make these codes strong and flexible,” says CII’s Roy Choudhury. But one cannot forget the burden of compliance, which is one of the biggest reasons why more than 85 per cent companies in India prefer to work in the unorganised space.

Focussing only on labour laws is a lopsided approach. “The government is assuming that reforming labour law is a panacea for economic ills,” says K.R. Shyam Sundar, Professor, Human Resource Management, XLRI Jamshedpur. “The government needs to think of the human development index, infrastructure and literacy rate, among other things,” he adds.

Take the case of Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra and Gujarat, which have attracted FDI not because of relaxed labour laws but due to availability of skills, infrastructure, energy, port connectivity and cheap land. Ease of doing business is not about rigidity of only labour laws, says Sundar.

Ritu Dewan, Vice President, Indian Society of Labour Economics, says government’s focus has been on the supply side. “The problem for the last two-three years has been the demand side, that people dont have money. Even before Covid-19, many companies were working at 20-30 per cent capacity. They were not producing as people were not buying.”

The consumption expenditure survey by the National Statistical Office shows that in FY18, consumer spending fell 3.7 per cent (for the first time in last 40 years) due to weak rural demand. The unemployment rate was at its highest since 1970s, at 6.1 per cent, between July 2017 and June 2018.

Since global demand has been hit hard, the country needs to think of ways to revive domestic demand. “It will come from public expenditure. The government has to look for ways to put money in pockets of those people who have the propensity to consume,” says Srivastava of IHD.